The sun is harsh in Mexico City.

Highlights burned, shade evil dark, and searing evil in the eye of the beholder.

As usual, our friends the film critics have been too long in the hot sun – and forgot to remove their shades come curtain-rise.

Scott gets a right rogering for his polished effort, a marathon held together (for you and me who lack sophistication) by a scorching blend of redeemed dispensing redemption.

Fortunately the paying popcorn public have attention spans greater than those panning pundits. And even Quinnell who authored the novel approved this adaptation.

Not a minute was wasted, nor any essential frame left on the cutting room floor. Two hours, twenty-six minutes of engrossing and carefully crafted tension.

Mexico City is the fall guy, its corruption implicit, the context given. While Daniel Eagan lands a blow: “Giving credit to Mexico City after spending two hours depicting it as the worst hellhole,” clear affection limned the capital before turning to its ugly underside.

And why did Lupita need be American, or her mum? Empathy might exalt authenticity beyond Scott’s wildest had he cast dark-eyed indigenous before brassy blondes.

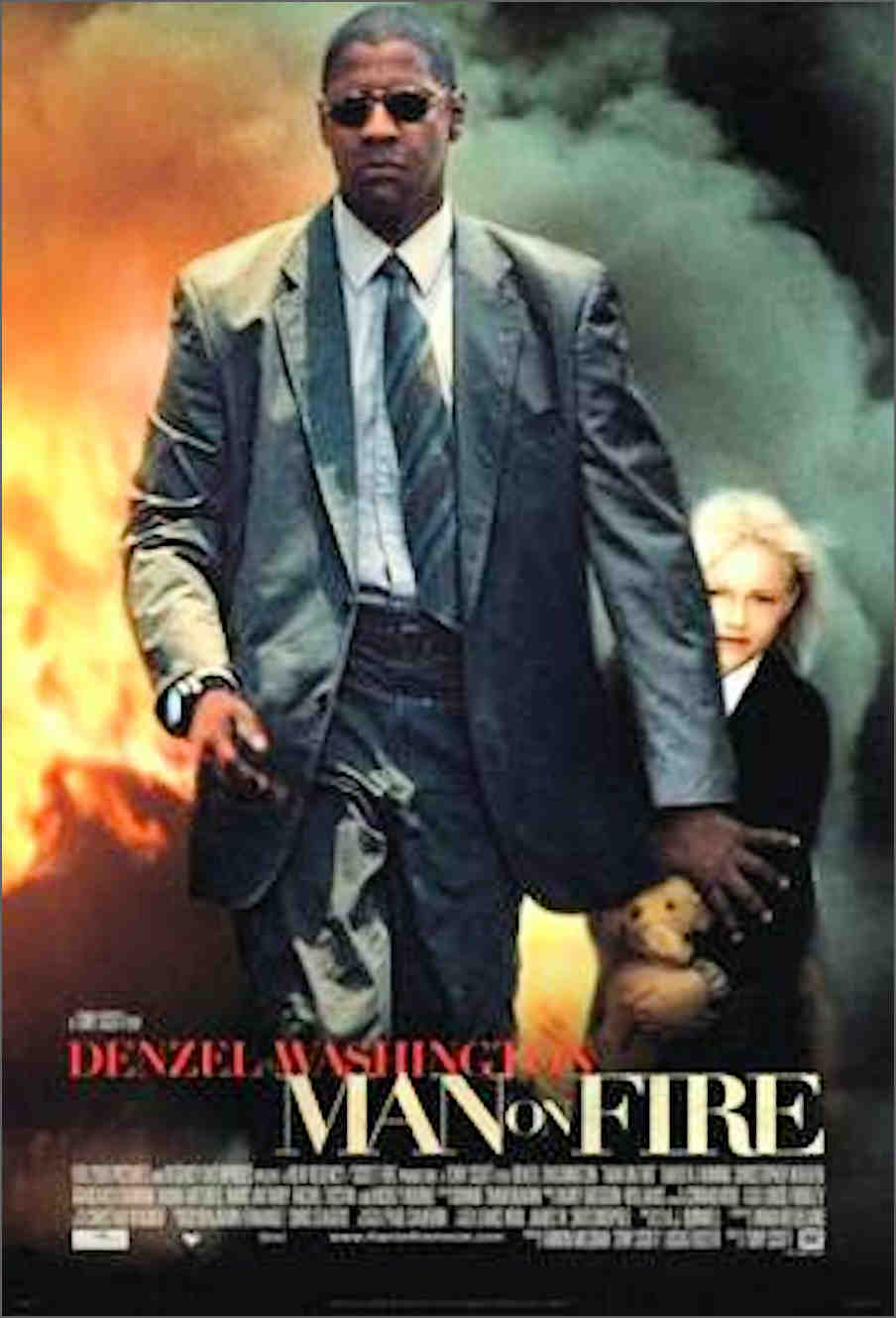

Man on Fire builds and builds, no looking back. It leads where we expect: to love, to lose, to go vigilante. Director Tony Scott knows his target better than specialist John Creasy (Denzel) his – and considerably more than professional box office bon vivants.

The movie is “heavy-handed and stiff, long-winded... jittery.... trash... meaningless(ly) stylistic... conventionally dopey action plot...”

To be a movie critic – let me remind those sadly deceived who forwent anticipated entertainment on the word of dire cynics – requires first that you lose faith in the message.

Our jaded critics reveal obsession with medium at expense of message.

Whilst we who watch films for pleasure lap up every moment of vintage Scott, Washington, Walken, and Fanning, our picky pundits see only “intrusive, fake-stylish camera tricks... jump cuts, sped up changes in light, colour, saturation and focal depth.”

Oh dear! Thank goodness I didn’t see any of that. What film were they watching? Sure, there was high-saturation, high-contrast interventions, by which documentary-like subliminals Scott shields our sensibilities from explicit and indecent violence.

We saw it, acknowledged the ploy, forgave, and urged him to proceed with the nasty lesson.

Treat yourself to this 2004 epic and you will notice upon the screen no hysteria, no hyperbole, little licence, nada neurotics — just professionals. All Creasy hears is “I’m a professional” – all you will see is professionals in economy, temperance, efficiency, taste and ambience. And time to reflect, a waning luxury in our modern hyper-active flicks.

As hero tales around the campfire did for the ancients, we impotent meek of this barbaric age find solace in comics of sweet revenge.