[Letter to the editor, Griffith Review 6 September 2007 – responding to Edition 13 ~ Author unknown]

The Next Big Thing inspired me to write concerning another demographic whose “political, social and creative agendas have been eroded by commercial imperatives, and turned into a commodity.”

I refer to the elderly, of whom I am one: an eighty-one-year-old survivor of the Great Depression, a veteran (in the VAD/AAMWS) of a war of genuine terror and peril, a mother and a grandmother. We begot the baby boomer generation, which begot Generations X and Y – and we are as homogeneous, so goes the hype, as are those younger groups that followed us.

In the best of all lands, we glide through life, smugly content with the world that we will leave to later generations.

That is the legend – and what a load of rubbish it is!

We are the generation that rejoiced in the defeat of Hitler and the Japanese Empire; that dared subsequently to dream, not of what we might one day own, but of the promised new world of peace and equity, a world without wars and poverty. We believed Australia was destined to continue as an example to the world, with its progressive agenda in social security, public education and health. We believed in a fair go for all.

It wasn’t perfect. There was the Cold War, then Vietnam; civil wars and famine in other countries; occasional transgressions by politicians or businessmen at home. But these were mere tacks in the wind; the final course was set by the light on the headland. We thought we could attend to our common business of humanity: working, loving, setting up homes and families.

In our old age we awoke, like Rip Van Winkle, to a world of Doublethink and Newspeak, with the economy replacing community and society as the main incentive in our lives.

When did ‘citizens’ become ‘customers’ of private enterprise and government? How did aged care, health care, child care and education become ‘industries’? And why did we so meekly acquiesce?

In our defence, we can plead that the change was cunningly wrought: first, denigration of the public providers and cutbacks in funding, with diversion to private entities; then fear campaigns regarding the quality and availability of the increasingly hard-pressed public services (health, education, aged care). Add to that blatant government policies encouraging the ‘private sectors’. The result – two standards of delivery to ‘clients’ – presented to a gullible public as a matter of ‘choice’, based on the ability to pay, fragmenting the last remnants of ‘community’.

Professionals (especially in health) are lured into the lucrative private sector, further degrading the public sector. This drift is boosted by expensive tertiary fees preventing graduates from entering the public sector, let alone doing pro bono work. State governments cop the blame for this shortage of specialists, engendered mostly by policies in Canberra.

Public hospital waiting lists lengthen for elective surgery (think agonising arthritis, blinding cataracts), so fearful pensioners pay for private cover, or spend their life savings on increasingly expensive procedures in the private sector. Private dentists’ fees are astronomical, but the national Dental Scheme was terminated in 1996. Medicare bulk billing rides a seesaw, and must be intermittently patched up by government tinkering.

Childcare, now largely privatised, has been described even by government members (e.g. Howard favourite Jackie Kelly) as ‘a shambles’: highly priced, often inappropriately situated, profit oriented, and its departmental administration confusing to customers. Overnight multimillionaires are the ultimate beneficiaries of massive taxpayer-funded subsidies in this industry.

State schools, once the democratising centres of communities, suffer as students attend highly subsidised (but often still expensive) private schools, which battle among themselves for brainier students.

Home affordability is at its lowest level since 1990 – due less to interest rates than to inflation, first-home-owner grants and a distorting tax system. Potential first home buyers and tenants share the agony of this; for many, rent or mortgage payments absorb up to 50% of income. Homelessness is at record highs, exacerbated by extreme cutbacks in government rental housing.

The irony is that the ‘housing boom’, the symbol of wealth at which the Treasurer danced a jig of joy, is an illusion. As mortgage sales increase, home owners may realise that the exponential increase in homes value is not real wealth; it only benefits investors or inheritors. If they’re lucky, Australians end up buying back into the same market in which they sell. Improper planning is another bad effect of the boom, with dire environmental consequences.

Two million Australians live in poverty, including many children. The real unemployment rate is probably double the official figure, but largely obscured by the amount of under-employment: 28% of jobs are casual and/or part-time, one of the highest rates in the developed world, and one hour’s work a week counts as employment. WorkChoices will likely worsen the situation. Leading church and welfare groups are rejecting the new Welfare to Work scheme as an attack on the most vulnerable.

I could go on. These matters concern many of my generation, and we discuss them at U3A meetings and over the internet.

We live in the real world. Not all our children and grandchildren are doing well; we fear for them, for all ‘ordinary’ people are just one push away from the precipice. In the present economic/social climate, only the very rich are immune.

What does this mean for the future? Greater division between rich and poor? More rampant consumerism funded by debt? Families finding their relationships in ever-narrowing circles decided by their children’s specialised schools? Increasing environmental degradation?

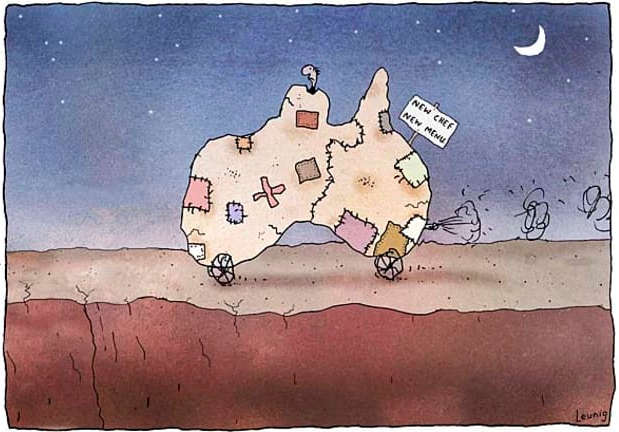

Is this the Australia we want?

No longer the land of a fair go for all but a nasty, dog-eats-dog place, a Hobbesian land where Margaret Thatcher’s ugly edict rules: “There is no such thing as society.”